Himalayan Sage Is the Salvia Collector's Holy Grail: Part 2

Plants don’t have voices but they have stories to tell, including tales of discovery. It’s easy to see why a plant explorer traversing broad expanses of northwestern India in the early 1800s would have paused to collect Himalayan Sage (Salvia hians), which is sometimes called Kashmir Sage.

Hians means “gaping” — a good description of the downward facing, open-mouth blossoms that seem to gawk. It’s an alpine meadow sage that grows wild at altitudes of about 9,800 to 12,500 feet where it blooms for months according to Flora of Pakistan (part of Harvard University Herbaria’s eFloras compendium of world floral data).

The online database reports that the species’ varying flower colors are “purple, violet, deep blue” and “rarely white.” As we mentioned in Part I of this article, Himalayan Sage sometimes is bicolor, such as in the well-known Chris Chadwell photo of a violet-blue variety with white lower lips.

Flora of Pakistan notes that the species is a “sturdy aromatic perennial” with foliage that is somewhat sticky and includes basal rosettes of cordate (heart shaped) or hastate (spear shaped) leaves. So, it looks pretty, smells good, is curiously viscous, and is strong enough to survive rough travel in a collection bag. How could French botanist Victor Jacquemont (1801 - 1832) resist it?

Naming History of Salvia hians

Perhaps the complete botanical name of Himalayan Sage should include the honorific jacquemontii, because the young Frenchman discovered it in Kashmir, India, sometime during his expedition from 1829 to late 1832 when he died. (Some sources say he succumbed to liver disease while others mention dysentery and malaria. All note exhaustion.) But the plant’s complete, formal name is Salvia hians Royle x Benth.

In 2012, Edward J. Valauskas, the curator of rare books for Chicago Botanic Garden, wrote a blog post highlighting CBG’s set of Jacquemont’s posthumous journals about his expedition — Voyage Dans l’Inde (Trip to India). He called Jacquemont “the most charismatic, tragic, and energetic natural historian of his generation.” Valauskas noted that Jacquemont’s botanical travels — first to America at 26 and later to India — were partly due to unrequited love for Italian opera singer Adélaide Schïasetti (1800 - ?) and his desire to escape France’s conservative military monarchy (part of Napoleon Bonaparte’s legacy).

According to Indian botanist Raj Kumar Gupta’s 1966 essay on Jacquemont in the Indian Journal of the History of Science, the French explorer collected 1,185 species throughout Jammu and Kashmir (a single Indian state) and the state of Punjab. But it appears that Dans L’Inde doesn’t mention any plant like S. hians or include any pictures resembling it among the 180 botanical illustrations in its fourth volume.

So, how do we know that Jacquemont brought this shade-loving, cold-tolerant plant to the attention of horticulture? The answer lies in the correction that another young botanist, George Bentham (1800 - 1884), made in 1833 to the first published description of the plant by British botanist John Forbes Royle (1798 - 1858).

Royle was superintendent of the British East India Company Botanic Garden in Saharanpur — a city in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh — at the time Jacquemont traveled the Himalayas. The “ex” in "Royal ex Benth." indicates that Bentham corrected one or more errors in Royle’s publication before republishing the plant in Hooker’s Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany.

To Royle’s credit, in his 1839 book Illustrations of the Botany and Other Branches of the Natural History of the Himalayan Mountains, he noted that Bentham’s publication set the record straight about Jacquemont having collected the sage.

Confusing Historical Illustrations

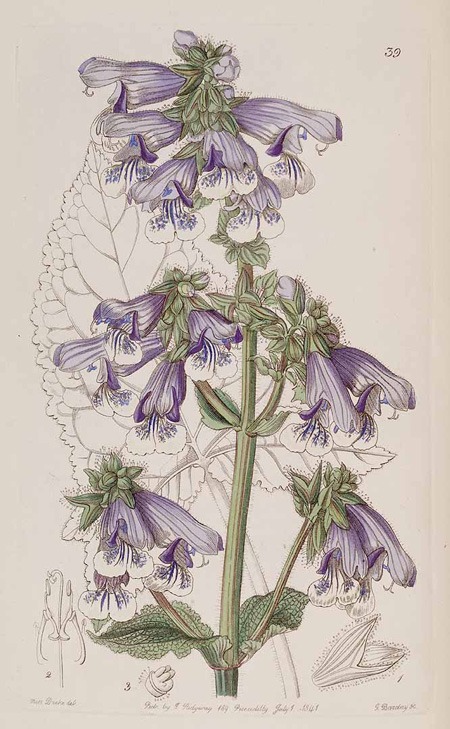

But what did the S. hians that Jacquemont collected look like? The first historical illustration of which we are aware appears in plate 75 of the second volume of Royle’s book. In opposition to the variety in Chadwell’s photo, each blossom of the plant in Royle’s book is white at the base and then flares into sky blue.

Seven public domain images from the 1800s, including the one from Royle’s book, appear at the non-commercial website plantillustrations.org. None look exactly like the variety in Chadwell’s picture or the type of Himalayan Sage (S. aff. hians ‘Elk Super Strain’) that we grow at Flowers by the Sea Farm. As explained in Part 1 of this article aff. stands for affinis, which means “closely related.” It’s safer to label our lovely variety affinis until genetic analysis of the species is available.

Seven public domain images from the 1800s, including the one from Royle’s book, appear at the non-commercial website plantillustrations.org. None look exactly like the variety in Chadwell’s picture or the type of Himalayan Sage (S. aff. hians ‘Elk Super Strain’) that we grow at Flowers by the Sea Farm. As explained in Part 1 of this article aff. stands for affinis, which means “closely related.” It’s safer to label our lovely variety affinis until genetic analysis of the species is available.

Perhaps the closest match for both Chadwell’s plant and the FBTS variety (minus the white lip) is the 1841 illustration from Edwards’s Botanical Register. One fine detail it captures, which you’ll also notice in our plant’s photo, is the halo of tiny hairs surrounding the calyxes.

Research about Uses in Healing

The search for new medicines has always been central to plant exploration. Both Jacquemont and Royle were interested in the folk medicine uses of the plants they collected. Jacquemont studied medicine in Paris before switching to botany. In contrast, Royle enrolled in medical school to pursue a career linking botany and pharmacology.

Many Salvias have a long history of use in folk medicine. S. hians is part of the medicinal Miltiorrhizae series (subdivision) of the genus. Other sages in this series include:

- Salvia bowleyana (Nan dan shen)

- Salvia glutinosa (Jupiter’s Distaff)

- Salvia miltiorrhiza (Dan shen) and

- Salvia nubicola (Himalayan Cloud Sage).

All are native to Asia (S. glutinosa is also a European native plant) and have red roots. S. miltiorrhiza is particularly popular in Asian pharmaceuticals.

In 2013, researchers from Garwhal University in Uttarakhand (a northern Indian state sometimes called Uttaranchal) and the Missouri Botanical Garden published a study in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine titled “Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garwhal Himalaya, India.” The Himalayan region is 1,500 miles long from Pakistan to its eastern boundary of Bhutan and includes a number of mountain chains, including the Garwhals.

The study states, “Himalayan forests are the most important source of medicinal plants...for the local people.” Kedernath includes high altitude meadows known in Uttarakhand as bugyals, which are home to medicinal herbs such as S. hians and S. nubicola. Concern about the impact of commercial grazing and tourism in the bugyals resulted in a successful August 2018 lawsuit (Aali-Bedini-Bagzi Bugyal Sanrakshan Samiti v. State of Uttarakhand and Others) to restrict those activities.

The study states, “Himalayan forests are the most important source of medicinal plants...for the local people.” Kedernath includes high altitude meadows known in Uttarakhand as bugyals, which are home to medicinal herbs such as S. hians and S. nubicola. Concern about the impact of commercial grazing and tourism in the bugyals resulted in a successful August 2018 lawsuit (Aali-Bedini-Bagzi Bugyal Sanrakshan Samiti v. State of Uttarakhand and Others) to restrict those activities.

In the Kedernath study, the researchers found evidence of S. hians’ leaf juice being used to treat arthritis, eczema, and body swelling. They cited anxiety, coughs, and colds as conditions treated using the plant’s roots.

In Nepal, the leaves of S. hians are used to heal eye infections according to a 2006 study published in the Nepalese journal Our Nature and titled “Use of Medicinal Plants in Traditional Tibetan Therapy System in Upper Mustang, Nepal.”

Of course, we at FBTS intend this information about folk remedies to indicate the medical promise of S. hians, but not to encourage home experimentation.

Rarity of Himalayan Sage

The Kedernath study identifies 18 plants in the reserve as being rare, including S. hians. The 2018 science book Himalayan Phytochemicals, published by Elsevier and written by Sumira Jan and Nazia Abbas, also describes S. hians as being rare. But what is botanical rarity?

The USDA Forest Service provides one of the best explanations we have found. It defines rare plants as being limited in quantity worldwide and states that this may be due to many reasons, ranging from human impacts (such as loss of habitat) to a distribution pattern naturally limited by a plant’s needs. Although rarity doesn’t equal endangered status, the Forest Service notes that plants which are uncommon have a greater chance of becoming extinct.

Genetic Plant Identification

In its first State of the World’s Plants report (2016), the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew) created a baseline record of known plants. It reported a total of 391,000 vascular species (the kind that have internal systems for conducting water and nutrients) of which 369,000 are flowering plants. However, it noted that whole genome sequencing was available for only 139 vascular species. A year later in its 2017 report, Kew reported that the number of genetically sequenced plants had risen to 225.

In 2017, Kew also announced success in field testing the complete genetic profiles of plants using portable nanopore technology. Maybe it won’t be too long before field testing is possible in the Himalayas. As Science Daily states in its article about Kew’s use of the technology, “Despite hundreds of years of taxonomic research, it is still not always easy to work out which species a plant belongs to just by looking at it.”

Growing Conditions and Other Questions

One question you may be pondering is whether you have the necessary growing conditions to invite Himalayan sages like our Salvia aff. hians ‘Super Elk Strain’ into your home garden. The answer is that you don’t have to live in an alpine setting to grow this perennial, yet it does need seasonal changes, including a chilly winter. This is great news for anyone in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 5.

You also need a partial shade location, such as a spot in the yard that gets morning sun and afternoon shade. S. hians and other Asian Salvias generally aren’t full sun, heat-loving plants. If your shady area is damp, that’s an added plus for this water-loving sage. Finally, it also needs loamy garden soil.

If we are out of stock for any of our Asian sages that interest you, we’ll be happy to email you when they are available. On a plant description page, just click the button that says, “Please notify me when this plant is back in stock.” Meanwhile, feel free to contact us if you have questions about any of the flowers in our online catalog. We have stories to tell.

Salvia aff. hians 'Super Elk Strain'

Salvia aff. hians 'Super Elk Strain'

Comments

There are no comments yet.